US-bound Ahmadi leader models a different kind of Islamic caliphate

(RNS) — As some 38,000 Ahmadi Muslims from more than 110 countries gathered in the countryside outside London this past August for the fast-growing denomination’s annual convention, thousands of Ahmadis camped out in tents less than a mile from a small house.

For the three days of the convention, or Jalsa, the modest building on Oakland Farm in Hampshire was the home of Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the Ahmadis’ spiritual leader, or caliph. In their nearby tent village, his followers gather to pray behind him and hear him speak on everything from women’s rights to achieving world peace.

“He might be the most accessible world religious figure,”

said Imam Abdun Nur Baten, an Ahmadi missionary serving in Paraguay who attended the Jalsa in the first week of August.

“He always keeps the door open. There is distance for logistical and security reasons, but you can visit him, get personal responses to your letters or find him praying in the mosque.”

Similar scenes may be repeated this month in the U.S., as the caliph will make his fourth visit to the United States’ estimated 20,000-strong Ahmadiyya community. Masroor Ahmad, whose last U.S. visit was in 2013, will make appearances beginning Oct. 15 in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Texas.

To Ahmadi Muslims, the term “caliph” comes without the dark connotations it has gained in the media, thanks to the Islamic State group and its vow to violently establish a worldwide caliphate. But Masroor Ahmad is no Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS.

Instead, in the 15 years of his caliphate, Masroor Ahmad, 68, has focused his followers on self-reformation and anti-extremism, warning that society is moving rapidly toward a dangerous fate due to its increasing injustice and immorality.

“During these days it is essential that we remain focused on prayer, as all of our success is based upon prayer,”

he told the crowd at the Jalsa.

“Our tasks and our mission can only be fulfilled through the grace of God alone.”

That mission is nothing political.

“For us, under the caliph, a victory doesn’t mean defeating or killing other people,”

Nasim Rehmatullah, an Ohio-based doctor who is vice president of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s U.S. branch, told Religion News Service.

“It means bringing them to our side.”

If Masroor Ahmad’s personable leadership style makes him an uncommonly accessible religious figure, his message has made him one of the most successful as well. The denomination has seen tremendous growth, adding more than half a million members this year to a worldwide body that already numbered between 10 million and 20 million.

Masroor Ahmad delivers his message from one of Europe’s largest mosques, Baitul Futuh Mosque in Morden, U.K., in sermons every Friday. He has also written several books and has spoken to members of Congress and the Parliaments of Britain and Canada.

Along with their adherence to a caliph, Ahmadis’ beliefs set them apart from other Muslims. Most Muslims consider Muhammad the final prophet, and say the caliphate, or

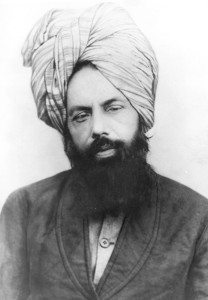

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad founded the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in 1889.

Muslim state, that began after his death (and continued through several sometimes disputed lines of succession from his closest companions to various Islamic emperors) ended in the early 20th century.

Ahmadis agree that Muhammad was the final law-bearing prophet. But they believe their denomination’s founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, born in 1835 in Qadian, India, was a subordinate prophet to Muhammad – a reformer who brought no new scripture. Many non-Ahmadi Muslim leaders see him as a false prophet and have branded Ahmadis heretics.

That has invited persecution, much of it violent. Ghulam Ahmad, a self-taught prolific writer and debater in favor of Islam, quickly gained followers in the Indian subcontinent when he claimed to be Islam’s promised messiah and reformer. But many local Islamic scholars did not take kindly to his claim, labeling him an apostate and calling for his murder.

After Ghulam Ahmad’s death in 1908 from natural causes, his followers believe that the caliphate was re-established.

The persecution ramped up as the community grew. In Indonesia in 2011, hundreds of Muslims wielding machetes, sticks and stones attacked an Ahmadi home, killing three men and maiming several others. In Algeria, more than 250 Ahmadis — 10 percent of the country’s Ahmadi population — have faced religion-related charges since 2016.

An Ahmadi shopkeeper in Scotland was stabbed to death in 2016, decades after zealots in Pakistan burned down his father’s pharmacy and hospital, forcing his family to flee to the U.K.

In Pakistan, where most Ahmadis are concentrated, the state has made it illegal for them to call themselves Muslim. Ahmadis are legally forbidden to use the traditional Islamic greeting of “Assalamu alaikum” (peace be upon you), to call their place of a worship a mosque or to congregate for the annual Jalsa. In the city of Gujranwala in 2014, a mob set an Ahmadi family’s home ablaze, killing one woman and two young children and causing a pregnant woman to have a miscarriage. In 2010, almost 100 Ahmadis were killed during attacks on two mosques in Lahore.

“There is no doubt that the Ahmadiyya community faces physical, social and legal threats in many countries where they reside,”

Johnnie Moore, an evangelical Christian pastor and a member of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, told Ahmadis in a speech at the Jalsa this year. In Pakistan,

“the rights of the Ahmadiyya community are consistently violated”

due to extreme blasphemy laws, he noted.

But Masroor Ahmad forbids any sort of violent retaliation.

Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the fifth and current caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, speaks to his followers at the Jalsa Salana on Aug. 4, 2018, in Alton, England.

When believers fully incline themselves toward God, he said in his opening Jalsa speech,

“then no politicians can hurt us, nor can any so-called Islamic scholars, nor can government officers … who are trying to making it harder for us to live in this earth.”

Born in 1950 in Rabwah, Pakistan, Masroor Ahmad studied agricultural economics at the Agriculture University in Faisalabad, Pakistan. He soon moved to Ghana, where he led social and agricultural development projects, and is credited with successfully cultivating wheat for the first time in the West African country’s difficult climate.

In 1985, he returned to Pakistan to serve the Ahmadiyya community in various senior administrative positions. He was briefly imprisoned for allegedly erasing words of the Quran from a sign, charges Ahmadis say are false and part of wider persecution against the denomination. In 2003, he was elected to succeed his uncle, Mirza Tahir Ahmad, as the community’s caliph.

Since then, Masroor Ahmad has launched a slew of public campaigns against extremism, an annual national peace symposium and an international peace award. He expanded the community’s disaster relief nonprofit Humanity First and oversees the building of free schools and hospitals around the world.

The Jalsa Salana site in Alton, England, hosted roughly 38,000 attendees in August 2018.

His focus on achieving world peace has drawn comparisons to Pope Francis. But Sarah Khan, a primary school teacher in Kingston, England, who attended the Jalsa, considers that a flawed analogy.

“The history of the papacy is concerned with power, wealth and land,”

she told RNS.

“But we see how humbly he lives. He takes no opportunity to aggrandize himself. He doesn’t want to meet his own ends; he wants to improve society as a whole.”

The climax of the Jalsa is the baiat ceremony, when Ahmadis form a human chain to take an oath of allegiance to their caliph. Dozens of new Ahmadis sit in a semicircle directly touching Masroor Ahmad, tears glinting on their faces.

He stretches his hand out to them and they repeat the pledges that initiate them within the Ahmadiyya denomination:

“I enter this day the Ahmadiyya Jamaat (Community) in Islam at the hand of Masroor … ”

Around the world, millions of Ahmadis repeat the words as they watch the scene on MTA, the denomination’s 24-hour TV channel.

Ahmadi Muslim men participate in the initiation ceremony, forming a continuous link to the caliph, at the Jalsa Salana in Alton, England, on Aug. 5, 2018.

Despite the community’s growth, many Jalsa attendees said, Ahmadis still share a deeply personal connection to the caliph. At The London Mosque, Masroor Ahmad’s followers wait in the rain, in lines wrapping around the block, hoping to pray as close behind him as possible. They even prostrate in the wet grass outside the mosque, where they might catch a glimpse of the caliph’s white turban as he returns to his office.

“Once you get hooked on the caliph, you’re totally changed,”

said Rehmatullah, who hasn’t missed a single Jalsa since the international convention began in 1984.

“I see the difference.”

Source: Religionnews.com